In August of 1948, Ruth traveled to Europe aboard the Zebulon Vance, a refurbished hospital ship. Aunt Ruth was always verbose, so I’m just taking the first part of her first letter from Austria. All photos are hers unless I note otherwise.

The Zebulon Vance. A refurbished hospital ship. Ruth wrote that the fastest speed was 12 knots–apparently the slowest troop transport. She was assigned bunk 13 in cabin C-2. There were 40 girls to a cabin with 2 showers. It took 15 days to cross the Atlantic from New York to Bremerhaven.

September 1, 1948

Linz, Austria

Hello Everybody!

The “blue” Danube

This is the first chance I’ve had to stay put in one place long enough to write a letter. Please excuse the carbon copies, but time doesn’t permit anything else. After five weeks of traveling I have finally arrived at my permanent station—Linz, Austria, an industrial town (steel, iron, salt, chemicals, textiles) of 180,000 population. We are billeted in the Linzerhof Hotel, and my window looks out over the “blue” Danube, which, incidentally, is a chalky green color. The Danube at this point marks the dividing line between the American and Russian zone and from my window I can look out on the Russian sentry at the end of the bridge.

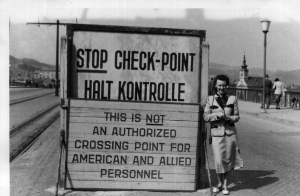

The bridge over the Danube. You can see the checkpoint between the Russian and American zones.

The Russian section. Ruth was here right after the Berlin airlift had started in response to the Soviet blockade of rail, road and water access to Allied-occupied areas of Berlin, so tensions were high between the Russians and other Allied forces at this time.

The whole trip has been most enjoyable, and I must give the Army credit for taking excellent care of us. We had expected to go to Bad Wiesse (30 miles out of Munich) for orientation with the German group of teachers, but found out as we were being processed on the ship that we were to go directly to Vienna instead.

The “Austrian delegation” of 11 teachers was the first to leave the Vance and walk across the docks to the military train waiting there. The train was a good one, our sleeper being a French coach. The first night the generator broke so we had no lights, but fortunately I had brought a flashlight along. We also had a “Spiesewagon” (diner) on the train. Only on American military trains do you find any food or water.

The trip from Bremerhaven to Munich was very interesting and shocking. As we passed through the extensive ruins of Bremen, Frankfurt, Stuttgart, Ulm, Augsberg, Munich, we realized what it meant to lose a war. All these railroad stations and almost everything around them were completely destroyed. If you can picture the Union Station in L.A. as nothing but a few tracks, some cement runways, no roof, and a few makeshift woode

Displaced Person train. There were still hundreds of thousands of displaced persons in 1948. Most had subsisted on 1,500 calories a day.

n shacks for luggage, you will have some idea of what many of the RR stations looked like. Their German civilian trains were badly overcrowded, the people very poorly dressed, and as we would leave the trains, hundreds of cold, curious, inscrutable, staring eyes would greet us. The Germans rarely smile and they are very quiet. The noisiest people in Germany and Austria are the Americans. I often wonder what the Germans and Austrians think of the noisy laughter and uninhibited remarks that the Americans make. I overheard one American girl remark that “Vienna reeks of culture!”

So this is where I pause and try to wrap my head around WWII and the aftermath in Europe. Aunt Ruth came ashore in Bremerhaven on August 18, 1948 after 15 days at sea crossing the Atlantic. She took a train from Bremerhaven to Munich. It was three years after the end of World War II. In 2016, I am the same age as she was at that time, and I have the benefit of 70 years having passed from then. We have solidified our history books about the time.

First, something light and interesting–carbon copies! I was irrationally annoyed at these wafer thin pieces of yellow paper until I realized the dedication it must take to write a letter. First of all–this is where “cc” comes from! It’s not just the place to put the email address of someone’s boss if you want to be passive aggressive! Secondly, this was the only way to make copies, so Ruth really had to prioritize who she wrote her very long letters to! Here’s a cool piece from Mental_Floss about carbon copies in case you are interested.

Back to the post-WWII analysis. While the physical carnage of the country must have been horrifying, it’s the people I am most interested in. What was behind those “cold, curious inscrutable staring eyes?” So this is where my inquiry could go several different ways. I’m starting by looking at the American approach to the Germans, or what Ruth refers to as the “occupation policies.” She learned these in her “indoctrination classes” aboard the Vance. Summarizing her class called, “You and the Germans,” she writes:

The general policy was “courteous firmness toward all the Germans.” We must be “firm, clear sighted, analytical, not overly sympathetic, but aware of the facts.” We should “show them the way of democracy by our lives.

I wish she would have kept some of the literature from these classes, but thus far I haven’t come across it. Here’s what I found doing some 21st century research (i.e. Google).

Initially, there was a strict non-fraternization policy for U.S. occupation troops. Photos of concentration camp victims were used as pictorial reminders. A 1944 version of a Handbook for Military Government in Germany recommended a quick restoration of normal life—I interpret that to mean that the Allied powers who occupied Germany would assist in economic reconstruction. When presented this, Franklin D. Roosevelt rejected it, saying:

Too many people here and in England hold the view that the German people as a whole are not responsible for what has taken place – that only a few Nazis are responsible. That unfortunately is not based on fact. The German people must have it driven home to them that the whole nation has been engaged in a lawless conspiracy against the decencies of modern civilization.

That military handbook was rewritten to be more consistent with the Joint Chiefs of Staff directive 1067, which stated “take no steps looking toward the economic rehabilitation of Germany or designed to maintain or strengthen the German economy.”

This approach to Germans was largely abandoned by 1947 with JCS 1779, which however it seems clears from Ruth’s description that the Army still emphasized the need to keep German civilians at arms length.

So that’s really interesting. Knowing Ruth, as I hope you all will come to do, I know that she was very principled and opinionated. I can imagine her following the directives from her army classes to the letter.

I’m new at this, so I’m going to start with questions. Maybe as I move through her journey, I will develop some conclusions.

First, did she look down upon these Germans—judging them for allowing some of the most horrendous atrocities the world has ever seen? My aunt was a very strong Christian, so the concept of forgiveness would have been an important element in her approach.

How would I have acted, knowing what I know—instead of just 3 years, having the benefit of 70 years of time passing since WWII?

What were those Germans really thinking? “Please don’t judge us—we really didn’t know.” “Why are you here? Hitler may have done some bad stuff but at least we could feed and clothe our kids.”

I’m going to head to the library to check out some books on this—Google can only do so much for me. Let me know if you have any good resource suggestions.

Thanks for trying this out. There are lots of things to think about and I’m only through half of her first letter. Next up–the “Red Carpet” was rolled out for Ruth and her colleagues when she reached Linz!

For now, bon voyage!

Comments are closed.